We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality,

tied in a single garment of destiny.

—Martin Luther King, Jr.

The wider world wouldn’t function were it not for networks. I often use ecological metaphor in my work, and one of my favorites is that of a redwood grove.

Redwoods are magnificent, inspiring trees for their height, longevity and beauty. Despite their stature, they actually have incredibly shallow roots and the only reason they are not routinely blown over by coastal winds and have been able to stand for centuries is that they grow in groves. Their roots weave together to form a mesh – some extending hundreds of yards – allowing them to remain upright.

So while we may look up and marvel at the height of individual trees, we should actually be awestruck looking down at the connections they have formed beneath the surface.

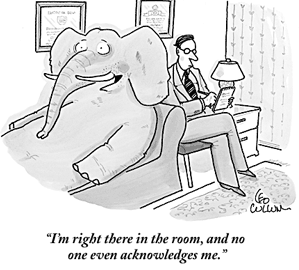

Similarly, in our views of leadership and institutions, we still lionize and celebrate the individual rather than the system. Archbishop Desmond Tutu has observed that “the fundamental law of human beings is interdependence: a person is a person through other persons.” However, our culture teaches us not to act that way.

While we claim to prize civility and structure laws to uphold it, our dominant education system and economic model enforce competition and create silos, all in a complex world where we need to act more like redwood trees and other ecological communities which thrive on collaboration.

Among the great challenges of our time is how we move from an era largely governed by the primacy of hierarchical models and institutions to one where networks become an increasingly critical form to create large-scale change.

Understanding network life stages and some practices to successfully navigate these transitions is vital – both for advocates and movement-builders in the social sector as well as among philanthropic institutions and the public and private sectors. As we evolve in this work, our attitude and orientation is most critical…as the late systems thinker and activist Donella Meadows shared:

“The scarcest resource is not oil, metals, clean air, capital, labor, or technology. It is our willingness to listen to each other and learn from each other to seek the truth rather than to be right.”

As with any ecosystem, a network moves through a series of stages with particular features. In the arena of sustainability, public health and social equity collaboratives — and generally applicable to other social change networks — I’ve seen these include:

- SEEDING. At the beginning of any network, a number of groups or individuals realize the need to come together around a perceived need that no one organization can achieve alone. Often this is a near-term threat or policy opportunity, though networks for social change are most effective when organized around a long-term vision. Like early life influences on an individual or ecosystem, the conditions and early members of a network can shape the trajectory and future characteristics of a network.

- GROWING. Relationships and an understanding of the issues involved within (and across) networks become richer and more complex as a network grows. With clear near-term outcomes and results, networks are able to attract resources (funding, members) to grow their efforts. The most important growth during this time is trust within the networks as individuals and institutions learn and work together.

- ROOTING. Once a network is “established”-though network membership and ecology is always changing, there is a sense of rootedness that develops: a dedication to a particular set of issues, a clear analysis of the system in which that network is operating, and operating guidelines that have evolved to build and sustain trust and network vitality.

- TRANSITIONING. It may be several months or several years-and, as with an ecosystem, change is constantly occurring-but all networks move into and through an evolutionary process. This time often brings up questions, even doubts, but network transitions (whether they are beginnings, bridges, or endings) are often the most fertile moments for understanding the real purpose and power behind our collaborative efforts.

Ultimately, these stages require those engaged in networks to act from a place that supports movement-building and community-rather than the success of any one organization’s mission. For in the end, if a network is modeled on a healthy ecosystem or healthy community, we must heed the words of Cesar Chavez, reminding those of us leading change that:

“We cannot seek achievement for ourselves and forget about progress and prosperity for our community. Our ambitions must be broad enough to include the aspirations and needs of others…for their sake, and for our own.”

This is one of my favorite “network poems” (and seasonally appropriate as well!):

The Seven of Pentacles

Under a sky the color of pea soup

she is looking at her work growing away there

actively, thickly like grapevines or pole beans

as things grow in the real world, slowly enough.

If you tend them properly, if you mulch, if you water,

if you provide birds that eat insects a home and winter food,

if the sun shines and you pick off caterpillars,

if the praying mantis comes and the lady bugs and the bees,

then the plants flourish, but at their own internal clock.

Connections are made slowly, sometimes they grow underground.

You cannot always tell by looking what is happening.

More than half a tree is spread out in the soil under your feet.

Penetrate quietly as the earthworm that blows no trumpet.

Fight persistently as the creeper that brings down the tree.

Spread like the squash plant that overruns the garden.

Gnaw in the dark and use the sun to make sugar.

Weave real connections, create real nodes, build real houses.

Live a life you can endure: make love this loving.

Keep tangling and interweaving and taking more in,

a thicket and bramble wilderness to the outside, but to us

interconnected with rabbit runs and burrows and lairs.

Live as if you liked yourself, and it may happen:

reach out, keep reaching out, but bringing in.

This is how we are going to live for a long time: not always,

For every gardener knows that after the digging, after the planting,

after the long season of tending and growth, the harvest comes.

Marge Piercy

In order to successfully navigate change, we need to build competencies as leaders that see us in relationship with those we work with in a different way. We need to build teams where everyone is able to bring their leadership to bear and hold ownership for results–as opposed to a single individual with ultimate authority and accountability. We have epidemic rates of Executive Directors and other senior leaders burning out or leaving the work and this does not help sustain morale or achieve the depth of change we seek.

In order to successfully navigate change, we need to build competencies as leaders that see us in relationship with those we work with in a different way. We need to build teams where everyone is able to bring their leadership to bear and hold ownership for results–as opposed to a single individual with ultimate authority and accountability. We have epidemic rates of Executive Directors and other senior leaders burning out or leaving the work and this does not help sustain morale or achieve the depth of change we seek.

I typically take a day a week to not turn on my computer, and we try to be selective about how much TV we take in. But I still frequently have my phone nearby, essentially a tiny screen where I stay tethered to more information than anyone could possibly process. In not using any technology for a few days, I noticed the increased presence I felt-both in connections to others, connections to what was happening around me, and connections to my own feelings -which is all usually there, but tempered by the ironic ability to “connect” at any point.

I typically take a day a week to not turn on my computer, and we try to be selective about how much TV we take in. But I still frequently have my phone nearby, essentially a tiny screen where I stay tethered to more information than anyone could possibly process. In not using any technology for a few days, I noticed the increased presence I felt-both in connections to others, connections to what was happening around me, and connections to my own feelings -which is all usually there, but tempered by the ironic ability to “connect” at any point.