What do we do if we are not trying to get something done and make our contribution, or tidy up, or be a better person?

What do we do with open space and unscheduled time?

We can rest, reflect, and play. We can, slowly and quietly, turn toward the joys of our existence, appreciate our friends and family, feel the unbearable lightness of our being, or gaze at the play of light and shadow on the wall.

We can allow the anxiety of relaxation, and then let it go.

We give the busyness a rest.

–Marilyn Paul

For years now, I have had a regular practice of not scheduling any work-related calls or meetings each Wednesday. I see it as both a luxury and a necessity. Working for myself, I’m largely able to set my own schedule and manage expectations around that while still delivering on my work. However, this is something that I advocate for-if not a whole day, then a half-day-for everyone I know.

We must take time to rest, reflect, play, and learn if we are to effectively care for ourselves and fulfill our purpose. It’s no secret that we live in a culture that is short on time and almost pathologically committed to producing “results.” Most people I know work too much and are pressured by their organizations and the system within which we operate-both the broader culture and the specific social sector orientation around urgency and emergency.

My practice of taking time on Wednesdays to catch up-sometimes this means working on clearing my inbox or having some focused time on a project, sometimes it means more time hiking out in the hills near my home and reconnecting (and often it is both)-and nearly fourteen years working as a (mostly) independent consultant encouraged me to think about a longer break to rest, recharge, and catch up with myself.

I stopped working in mid-December and returned-slowly-in mid-to-late February. As sabbaticals go, it wasn’t the longest amount of time: most books on the topic will recommend a minimum of 3 months. Yet it was what I was able to manage.

Beyond what I did–traveled to Thailand with my family, took a week by myself on retreat, did a lot of yoga and exercise, spent time in the woods with my dogs, had more time to spend with family and friends–my sabbatical infused me with the rest I needed and the perspective on how to weave this into my life while invested deeply in the work I love.

Beyond what I did–traveled to Thailand with my family, took a week by myself on retreat, did a lot of yoga and exercise, spent time in the woods with my dogs, had more time to spend with family and friends–my sabbatical infused me with the rest I needed and the perspective on how to weave this into my life while invested deeply in the work I love.

I returned from sabbatical with a few clear lessons and some deeper meaning that I still cannot quite describe. These lessons are all in the realm of the obvious-though I (and many of us, I’m sure) are often challenged to acknowledge and embrace them in our lives:

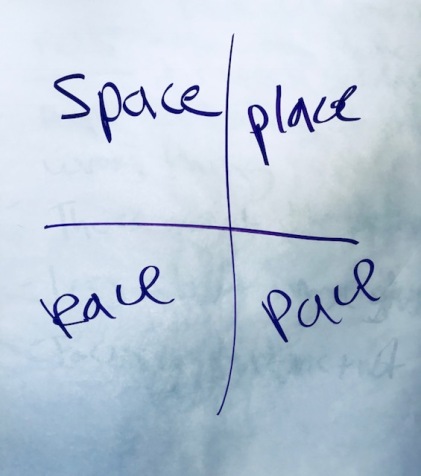

- Take time for renewal/create space in each day.This means spaces to do nothing and just pause (meditation, sleep, staring at the wall, a walk around the block or in nature) and time to move and reconnect with ourselves and our bodies (going for a run, to the gym, to a yoga class). There is also a way in which we can weave a different pace into our days-no matter how busy we may be. For me, that means trying to not schedule calls one after the other, choosing reasonable start and stop times for work (including not working at nights or on weekends), and checking e-mail at prescribed times. Most importantly, it is about having ways to check in and catch myself if I feel that I’m getting distracted or overwhelmed.

- Schedule regular time for “maintenance.” In addition to space for renewal, I realized that I had let time slip away for regular maintenance (meeting with a coach or therapist, doing something you love like playing music or gardening, going to the acupuncturist, treating myself to a massage, scheduling a mini-retreat). Often, we can feel that if nothing is “wrong” we don’t need to worry about doing this kind of care-yet we need periodic (each week, month, quarter) time for these activities.

- Take a break from social media/digital detox. I cannot overstate the level of calm and spaciousness that an occasional (or permanent) digital detox can create. Before my sabbatical, I got off of all social media and put those apps in a folder buried on the fourth screen on my phone. I turned off all notifications, other than texts and voicemail. I still have not been back on social media or re-enabled those notifications. I still have my accounts to occasionally share posts (like this newsletter), but am conscientious about how I visit and interact with social media sites…and like the practice of looking at my e-mail rather than being beckoned by those little red circles that tell you messages are waiting!

You may find these challenging because of the patterns we have established and the demands that your work or family might place on you. Negotiate for even a little time–many workplaces have sabbatical policies (or are developing them) and understand that schedule changes are the key to retention. If you don’t already, figure out how to put time on the family calendar that is just for you…often a regular class allows for that and encourages you to commit to a fixed schedule for taking this time.

You may find these challenging because of the patterns we have established and the demands that your work or family might place on you. Negotiate for even a little time–many workplaces have sabbatical policies (or are developing them) and understand that schedule changes are the key to retention. If you don’t already, figure out how to put time on the family calendar that is just for you…often a regular class allows for that and encourages you to commit to a fixed schedule for taking this time.

Beyond these more obvious practices that many of us know to do (and are either successful at or on a path to incorporating them more regularly), a sabbatical of any length-a day, a week, a few months, a year-can create a stronger connection with our sense of purpose and open up possibilities for transformation.

I’ve been able to maintain a sense of calm many weeks into my return, even when the challenges of work and life arise. I also feel a more profound identification with and responsibility toward the work that is central to my purpose: to support authentic connection in the world in service to addressing our greatest challenges around environmental issues, community-building, and racial justice and social equity.

This is meaningful in how I show up with those I am in partnership with now, and also has implications for the future of my work. While this might not be entirely clear, my sabbatical reconfirmed and deepened my confidence and excitement about the path I am traveling in the world.

A sabbatical of any length creates a separation when we focus on ourselves…and this can paradoxically connect us even more effectively to the broader world and the changes that might come from cultivating more quiet.

This is one of my favorite poems that speaks to that possibility…

Keeping Quiet

Now we will count to twelve

and we will all keep still

For once on the face of the

earth,

let’s not speak in any language;

let’s stop for a second,

and not move our arms so much.

It would be an exotic moment

without rush, without engines;

we would all be together

in a sudden strangeness.

Fishermen in the cold sea

would not harm whales

and the man gathering salt

would not look at his hurt hands.

Those who prepare green wars,

wars with gas, wars with fire,

victories with no survivors,

would put on clean clothes

and walk about with their brothers

in the shade, doing nothing.

What I want should not be confused

with total inactivity.

Life is what it is about.

If we were not so single-minded

about keeping our lives moving,

and for once could do nothing,

perhaps a huge silence

might interrupt this sadness

of never understanding ourselves

and of threatening ourselves with

death.

Perhaps the earth can teach us

as when everything seems dead in winter

and later proves to be alive.

Now I’ll count up to twelve

and you keep quiet and I will go.

Pablo Neruda

The poet Patrick Cavanaugh has written that “Sometimes the truth depends upon a walk around the lake.” The time we take to authentically connect can bring us closer to the truth-whether that is our own, or shared understanding in a team or community.

The poet Patrick Cavanaugh has written that “Sometimes the truth depends upon a walk around the lake.” The time we take to authentically connect can bring us closer to the truth-whether that is our own, or shared understanding in a team or community.